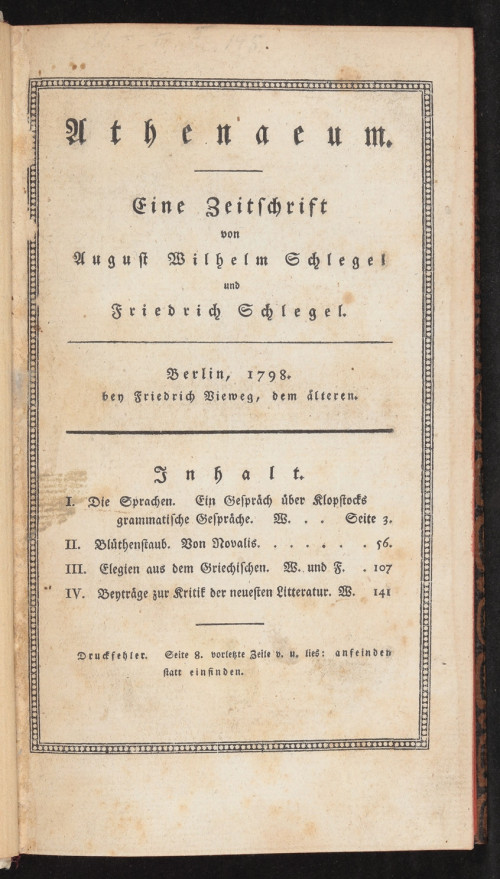

In 1798, the brothers August Wilhelm and Friedrich Schlegel founded the Athenaeum, the only literary journal of the early Romantic era. By the summer of 1800, six issues had appeared. Most of the contributions were by the two brothers themselves, the remaining texts by their partners Dorothea Veit and Caroline Schlegel, the poet Novalis, and the theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher. Collective writing and philosophizing became key elements of their pursuits: “Perhaps a whole new epoch of science and art would be inaugurated, if symphilosophy and sympoetry were to become so common and deeply felt that there would be nothing odd about several people of mutually complementary natures creating works in communion with each other.” Thus begins Fragment 125.

Programmatic statements are found throughout the issues of the Athenaeum. Fragment 116, for example, proclaims: “Romantic poetry is progressive, universal poetry.” And further on in the text: “Romantic poetry is still evolving; indeed, its very essence is that it is always evolving and can never be considered perfected.” These sentences formulate the core ideas of Romanticism: What is separate is to be brought together, and “poetry” can unite everything within itself. And because it is quite an ambitious programme, one never reaches the finish.

Novalis’s Pollen fragments likewise lend expression to the romantic self-conception: “We seek the absolute everywhere and only ever find things.” And somewhat further on: “The mysterious path leads within.”

Important points of reference for the Athenaeum were Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship and Johann Gottlieb Fichte’s philosophy of the self, according to which reality is created solely through the perception of a subject.

The unconventional living situation that came about in Jena also encouraged the ongoing mutual exchange among the members of the group. August Wilhelm and Caroline Schlegel, who had brought her daughter Auguste Böhmer with her into the marriage, lived in a house in Leutragasse. In the autumn of 1799, Friedrich Schlegel, his partner Dorothea Veit, a divorced Jewess, and her little boy Philipp moved in as well. Friends often came to visit, further widening the convivial circle. Not only Novalis, Schelling, and Ludwig Tieck but also Sophie Mereau and Clemens Brentano, for example, were always welcome.

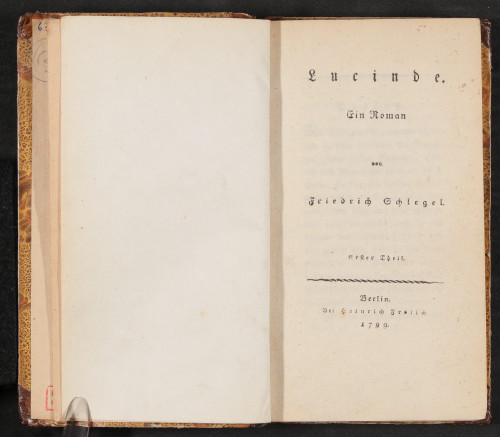

This living and working community, which is portrayed in a short film in the peep box, was quite exceptional for the time, and caused a sensation. And Friedrich Schlegel added fuel to the furore in February 1799 when he published his novel Lucinde about an unconventional romance. The work became a scandal because it was thought to reveal the author’s own love life.

The Romantics doled out harsh criticism and scathing sarcasm — and also earned both in return. The caricature Versuch auf den Parnass zu gelangen (Attempt to Scale Parnassus) came out in 1803. It shows the Schlegel brothers and their comrades striving to reach the throne of the god Apollo and the muses, above which the successful writer August von Kotzebue floats on a cloud.

The communal life in the Jena flat came to an end in 1800. August Wilhelm Schlegel and his wife moved out and went separate ways; Caroline Schlegel became involved with Schelling. Friedrich Schlegel and Dorothea Veit also left the house, but initially remained in Jena before getting married in Paris in 1804.

The unusual house share, the novel Lucinde, and the journal Athenaeum were bold experiments, and unique for their time. Life and art were no longer separated, but deliberately mixed.

Objects

-

AUGUST WILHELM SCHLEGEL, FRIEDRICH SCHLEGEL

Athenaeum. Eine Zeitschrift von August Wilhelm Schlegel und Friedrich Schlegel

6 Hefte in 3 Bänden. Berlin: Vieweg 1798; Berlin: Frölich 1799–1800.

-

FRIEDRICH SCHLEGEL

Lucinde. Ein Roman von Friedrich Schlegel

Berlin: Frölich 1799.

-

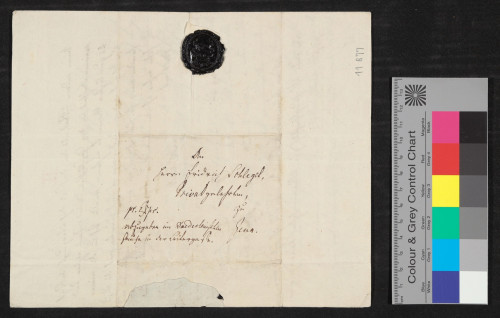

AUGUST WILHELM, FRIEDRICH UND CAROLINE SCHLEGEL

Letter to Friedrich von Hardenberg (Novalis), Dresden, July 1, 1798

-

FRIEDRICH VON HARDENBERG (NOVALIS)

Letter to Friedrich Schlegel, Tennstedt, May 3, 1797

-

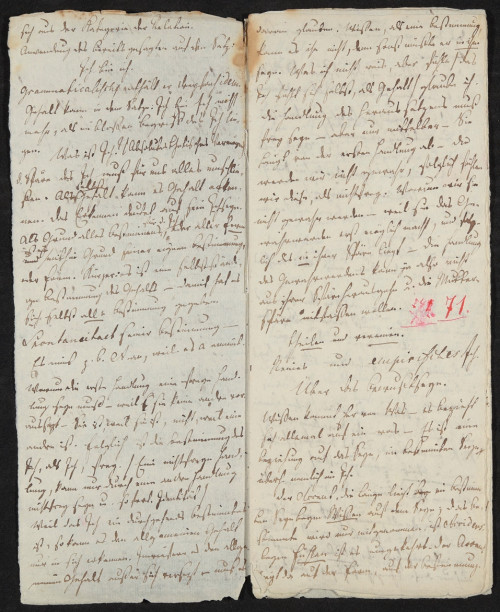

FRIEDRICH VON HARDENBERG (NOVALIS)

Bemerkungen, Autumn 1795

-

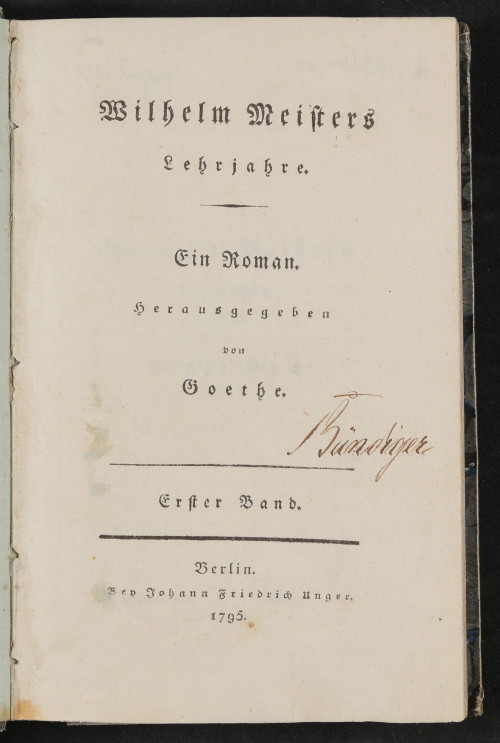

JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHE

Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre. Ein Roman. Herausgegeben von Goethe

Band 1 (von 4). Berlin: Unger 1795.

-

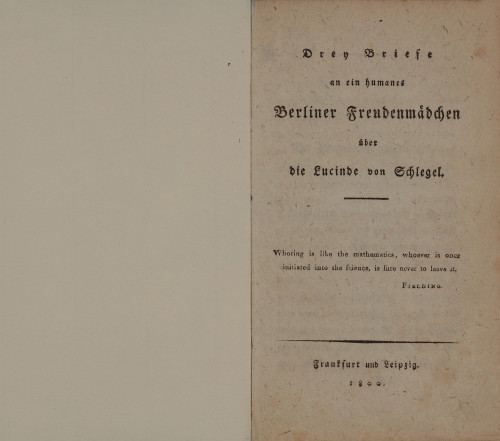

ANONYM

Drey Briefe an ein humanes Berliner Freudenmädchen über die Lucinde von Schlegel

Frankfurt a. M. und Leipzig: Nauck 1800.

-

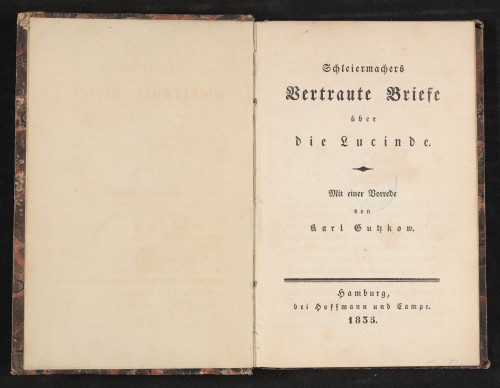

FRIEDRICH SCHLEIERMACHER

Schleiermachers Vertraute Briefe über die Lucinde. Mit einer Vorrede von Karl Gutzkow

Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe 1835.

-

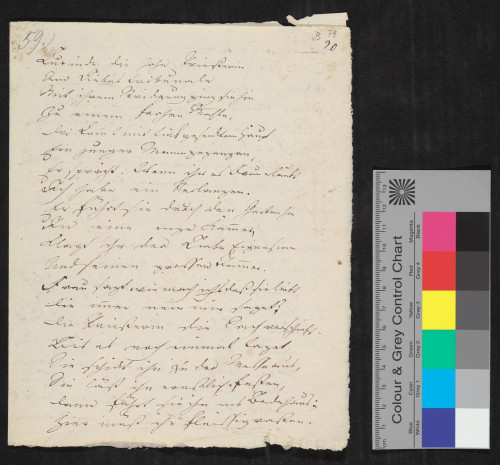

ACHIM VON ARNIM

Lucinde die hohe Priesterin, 1802