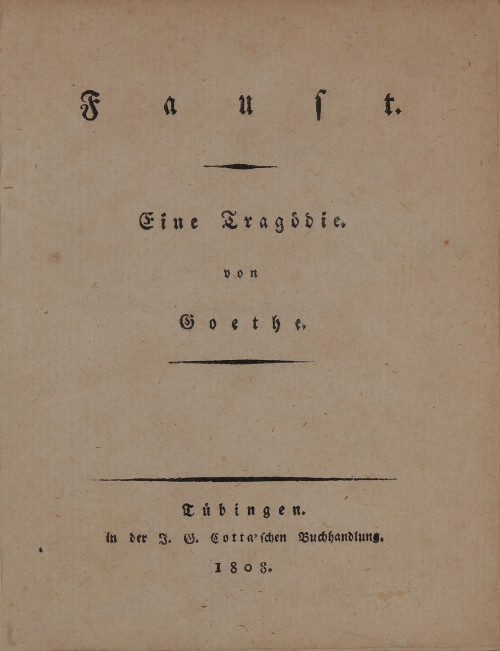

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s tragedy Faust came out in 1808. He had already begun work on the play as a young man in Frankfurt am Main, but then put it aside for many years. For the cover of the partial publication in 1790 under the title Faust: A Fragment, he had chosen an engraving by Rembrandt. He wanted the edition of 1808, however, — containing the entire part one of the tragedy — to be published without illustrations. As early as 1805, he had written to Cotta, his publisher: “I thought we should publish Faust without woodcuts or illustrations … I think the sorcerer must make do on his own.”

The play attracted wide attention when it was published. Goethe had revived the historical figure of Doctor Faust, who had lived in the Late Middle Ages, and cast him as a complex, modern character. Discontent with his life as a scholar who experiences life only in books, Faust enters into a pact with the devil, Mephistopheles, who grants him new youth. His love affair with Gretchen follows, and ends in disaster: pregnant out of wedlock, she kills the child after its birth, and the final scene has her in a dungeon awaiting her execution.

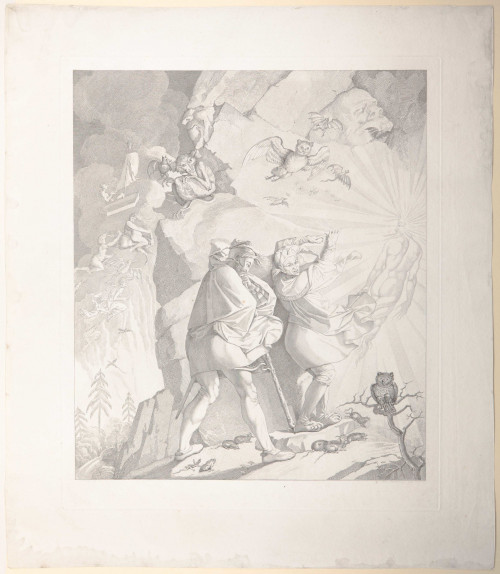

Particularly visual artists found inspiration in Goethe’s text. It was Peter Cornelius who created the first prominent illustrations. Born in Düsseldorf in 1783, he had studied at the art academy in his native town. He came to Frankfurt in 1809, and it was there that he began the drawings for Faust. Taking the art of Albrecht Dürer as an orientation, he created romantically tinged images of medieval settings and figures.

Goethe first saw Cornelius’s drawings in 1811 and expressed his approval. He advised Cornelius not to look solely to the first series of twelve etchings got underway in 1816, the artist was already living in Rome. The prints were a huge success for Cornelius — the Neogothic style suited the tastes of the day and would shape the popular image of Goethe’s Faust for a long time to come.

In 1826, Goethe saw initial proofs of the Faust illustrations by the French Romanticist Eugène Delacroix. He was fascinated by the striking scenes peopled with figures full of passion and ambivalence. In his words, they even “surpassed his imagination”.

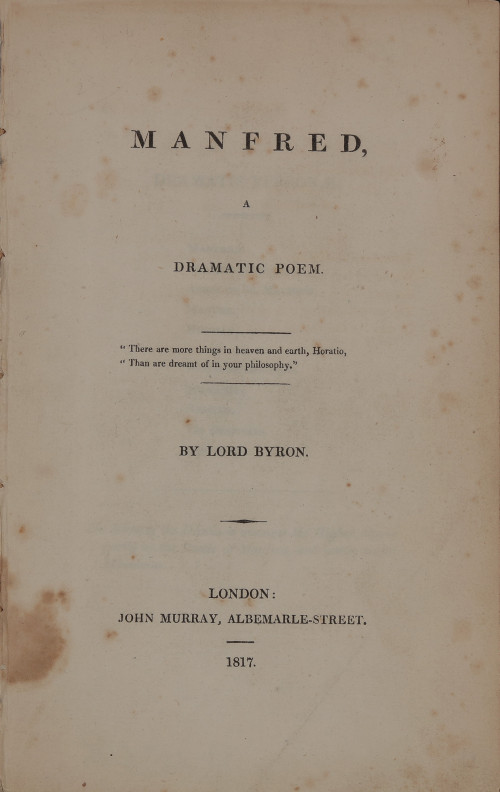

Goethe’s Faust also inspired writers. The English Romanticist Lord Byron clearly borrowed from the tragedy for his poem Manfred. Goethe reacted sympathetically and in turn took inspiration from the Englishman’s work for his Faust sequel.

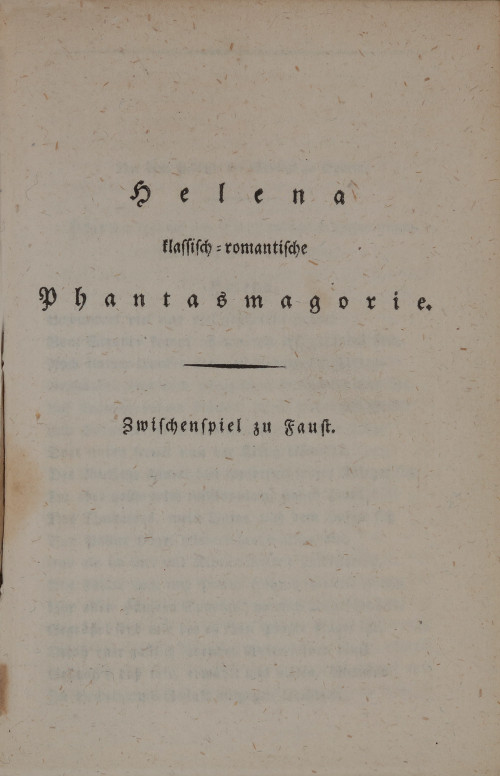

Faust, Part Two did not appear in print until after Goethe’s death — except for one act, published in 1827 under the title Helena: Classical-Romantic Phantasmagoria. In Goethe’s day, the word “phantasmagoria” — which means “delusion” or “apparition” — was used to refer to the ghostly images projected onto theatre stages by a magic lantern. The subtitle points to the goal Goethe attached to his work: that it should help resolve the dispute between Classicists and Romanticists meanwhile raging all over Europe.

Objekte

-

FRANZ LISZT

Faust Symphony, 1854–1857

Ausschnitte aus Faust (1. Satz), Gretchen (2. Satz), Mephistopheles (3. Satz). Klaus König (Tenor), Gewandhausorchester Leipzig. Leitung: Kurt Masur. Eterna 1981

-

JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHE

Faust. Eine Tragödie. von Goethe

Tübingen: Cotta 1808.

-

PETER CORNELIUS

Bilder zu Göthe’s Faust, 1816‒1826

-

JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHE

Helena klassisch-romantische Phantasmagorie. Zwischenspiel zu Faust

In: Goethe’s Werke. Vollständige Ausgabe letzter Hand. Band 4. Stuttgart und Tübingen: Cotta 1827, S. 229‒307.

-

GEORGE GORDON BYRON

Manfred, A Dramatic Poem. By Lord Byron

London: Murray 1817.

-

EUGÈNE DELACROIX

Illustrations to Goethe's Faust

In: Faust, Tragédie de M. de Goethe, traduite en français par M. Albert Stapfer, Ornée d’un Portrait de l’Auteur, et de dix-sept dessins composés d’après les principales scènes de l’ouvrage et éxécutés sur pierre par M. Eugène Delacroix