Rahel Levin was born in Berlin in 1771 to a prosperous Jewish family. As a Jewess and a woman, she was denied equality twofold. Shortly before her marriage to the considerably younger diplomat Karl August von Varnhagen, she converted to Christianity and was baptized Antonie Friederike. During her lifetime, all of her publications — primarily letters and aphorisms — were published anonymously.

A highly educated woman, Rahel Levin was known above all for the private tea parties she hosted from the 1790s onwards. There she brought together a convivial circle of relatives, friends, intellectuals, politicians, and members of the nobility. Over the years, there were also numerous Romantics among her guests. The gatherings were characterized by openness and tolerance: what counted was the individual, not his or her sex, social status, or religious affiliation. It was in this period that the sculptor Friedrich Tieck executed his portrait relief of the 25-year-old salonnière. She herself thought it resembled her “quite closely”.

An illustration by the artist Erich Simon dating from the year 1923[SK1] conveys an impression of her salon culture. Rahel Levin’s first salon, the “garret” in Jägerstrasse, came to an end in 1806 when Prussia succumbed to Napoleon’s troops, and a phase of economic hardship ensued. The mood was largely anti-French and anti-Jewish, as was also the case with the “German Table Society” co-founded by Achim von Arnim.

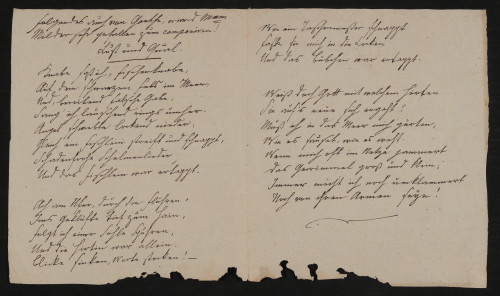

The next several years kept Rahel and Karl August Varnhagen moving from one town to the next — he was in the diplomatic service. The couple returned to Berlin in 1819, where she was finally able to begin hosting her second salon. From the start, her enthusiasm for Goethe played a role in her salon, and it was he to whom she dedicated her first publication: On Goethe: Excerpts from Letters. Drawer number 1 contains Rahel Varnhagen’s transcripts of two Goethe poems evidently intended for the song composer Jeannette Milder.

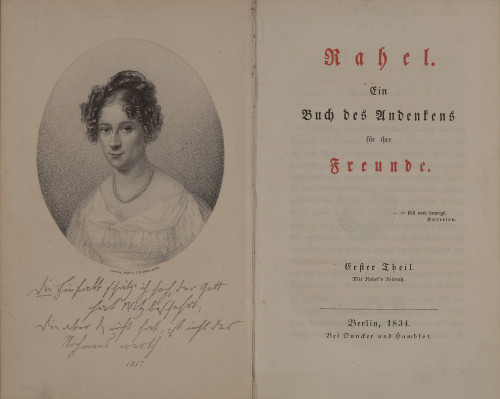

With a collection of letters entitled Rahel: A Memorial Book for Her Friends, Karl Varnhagen erected a monument to his wife and her progressive utopia of free conviviality. Containing correspondence with some 130 contemporaries, the volume testifies to her as an intellectually emancipated writer whom Heinrich Heine declared the “most brilliant woman of the universe”.

All her life, Rahel Varnhagen suffered from the widespread hostility towards Jews. Even among her guests there were some who elsewhere expressed anti-Semitic sentiments. She was horrified by the anti-Jewish pogroms, the so-called Hep-Hep riots of 1819, involving violent excesses against Jews in many cities of the German Confederation. The attacks targeted efforts to grant Jews equality before the law. She wrote: “I am infinitely sad on account of the Jews, in a way I have never experienced before. What should this mass of people do, driven out of their homes? They want to keep them only to despise and torture them further … to kick them and throw them down stairs.”

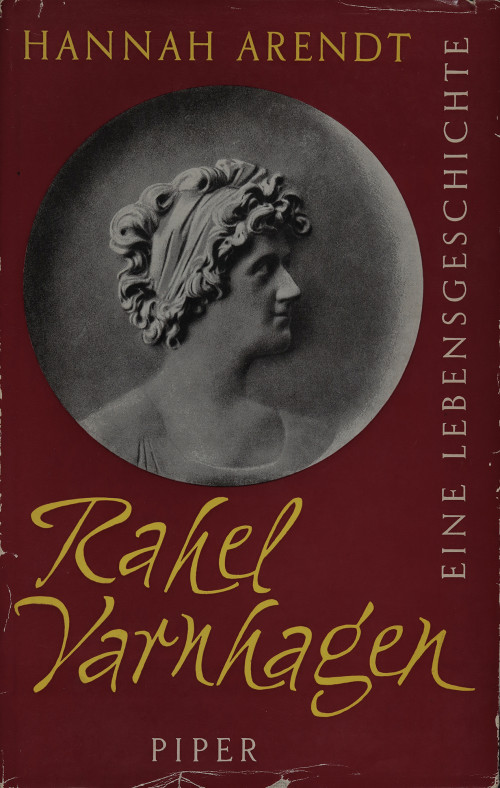

Drawer 2 holds the biography by the philosopher Hannah Arendt, who interpreted Rahel Varnhagen’s life from the perspective of a German Jewish woman after the Shoah.

Objects

-

LOUIS FERDINAND PRINZ VON PREUSSEN

Larghetto G-Dur, Op. 11, 1806

Göbel-Trio Berlin. Thorofon 1990

-

RAHEL VARNHAGEN

Rahel. Ein Buch des Andenkens für ihre Freunde

Teil 1 (von 3). Berlin: Duncker und Humblot 1834. – Frontispiz (Stahlstich in Punktmanier) von Carl Eduard Weber nach Moritz Michael Daffinger, darunter Rahel Varnhagens faksimilierte Handschrift: „Die Einfalt schätz’ ich hoch, der Gott / hat Witz bescheh

-

CHRISTIAN FRIEDRICH TIECK

Rahel 1796 (1835)

-

RAHEL VARNHAGEN

Copy of two poems by Goethe, nach 1820

S. 1: Merz („Es ist ein Schnee gefallen“), S. 2: Lust und Qual („Knabe saß ich, Fischerknabe“) mit der Anmerkung: „Folgendes auch von Goethe, wird Mam Milder sehr gefallen zum componiren!“, auf S. 4 von unbekannter Hand: „Rahels Hands

-

HANNAH ARENDT

Rahel Varnhagen. Lebensgeschichte einer deutschen Jüdin aus der Romantik. Mit einer Auswahl von Rahel-Briefen und zeitgenössischen Abbildungen.

München: Piper 1959.