In 1802, Philipp Otto Runge put the situation of his generation in a nutshell: “With us, too, something again is perishing; we stand at the edge of all religions, … the abstractions are dying away, everything is airier and lighter than what came before, everything presses towards landscape, seeks something definite in this indeterminacy, and does not know how to begin it.” At such an epochal turning point, recourse to the already existing was no longer an option. Now it was up to each individual to forge his or her own path; greater liberties went hand in hand with greater uncertainties.

This was also true of how artists conceived of themselves. The nobility and the Church no longer commissioned art on a grand scale; artists’ workshops had been replaced by academies, which trained so-called “free artists”. Among the various genres, especially landscape painting offered latitude. Yet art also found new forms for the portrait, the interior, and the history painting, which could now also incorporate a subjective outlook.

The academy in Dresden established a professorship for landscape painting. And the city had a rich artistic environment to offer outside the academy as well. In this context, Caspar David Friedrich was a key figure. His paintings elicited as much enthusiasm as they did incomprehension, even aggression. In Vienna, a group of art students rebelled against academic traditions and moved to Rome. They called themselves the “Brotherhood of Saint Luke” but would come to be known as the “Nazarenes”. Drawing on the Renaissance and the Middle Ages, they combined life and work. Rome offered fertile ground for artistic experimentation: artists from all over Europe tried out new techniques and subject matters there, and engaged in lively exchange.

Romanticism is anything but a homogeneous movement. It is characterized more by the open question than the definitive answer. Here art is a form of communication: it manifests itself in small oil studies and huge frescoes, delicate pencil sketches and classical oil portraits. It finds its abode as much in the little town of Weimar as in Rome, Paris, and Dresden. Craftsmanship and mastery no longer suffice; Romanticism believes in artists who stand up for their art with mind, body, and soul — an idea that has endured to the very present.

Objects

-

Carl Gustav Carus

DEUTSCHER MONDSCHEIN

1833

-

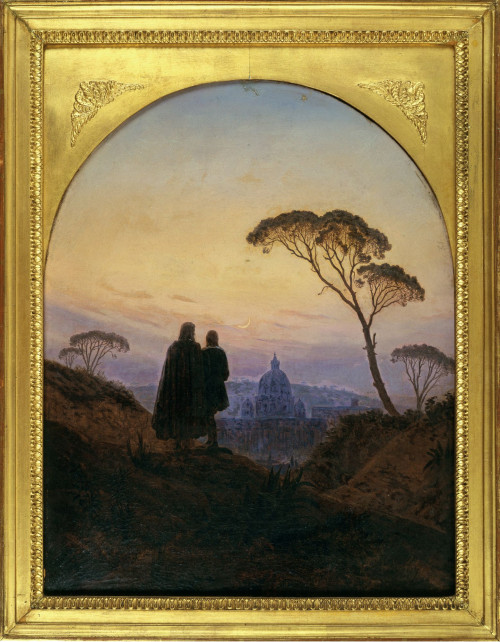

Carl Gustav Carus

ERINNERUNG AN ROM I

1831

-

Carl Gustav Carus

ITALIENISCHER MONDSCHEIN

1833

-

Johann Christian Klengel

DORFKIRCHE VON PLAUEN

-

Carl Gustav Carus

VERSCHNEITER WALD MIT STEINKREUZ

1823

-

Carl Gustav Carus

ELBINSEL BEI PILLNITZ

Um 1832/34

-

Caspar David Friedrich

DER ABENDSTERN

1830

-

Caspar David Friedrich

WEIDENGEBÜSCH BEI TIEFSTEHENDER SONNE

Um 1832/35

-

Caspar David Friedrich

SCHWÄNE IM SCHILF

Um 1819/20

-

Carl Christian Vogel von Vogelstein

DAVID D’ANGERS MODELLIERT DIE BÜSTE LUDWIG TIECKS

1836. Dauerleihgabe der Bundesrepublik Deutschland.

-

Ernst Ferdinand Oehme

TAL VON FINSTERMÜNZ IN TIROL

1830

-

Johan Christian Clausen Dahl

DER VESUV, GESEHEN VOM POSILLIPO

1847

-

Carl Blechen

DER VESUV

1829. Dauerleihgabe der Bundesrepublik Deutschland.

-

Carl Ludwig Kaaz

RÖMISCHE LANDSCHAFT BEI TIVOLI

Um 1802/04

-

Ludwig Emil Grimm

MELINE VON GUAITA GEB. BRENTANO

1820. Dauerleihgabe aus Privatbesitz.

-

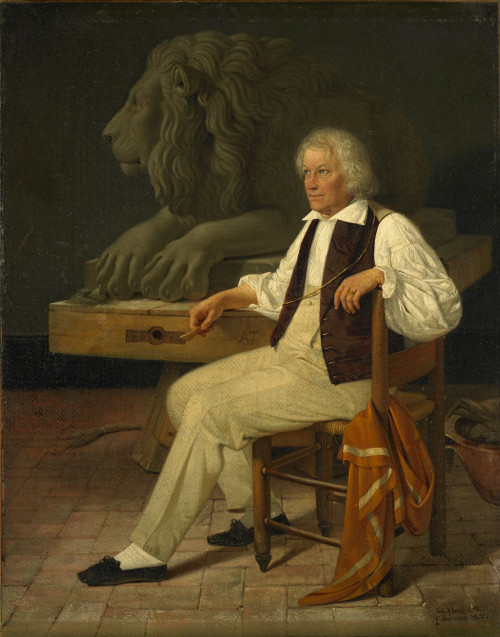

Detlev Conrad Blunck

BERTEL THORVALDSEN IN SEINEM RÖMISCHEN ATELIER

1837

-

Ferdinand Jagemann

DIE HEYGENDORFFSCHEN KINDER

1812

-

Louise Seidler

JULIE ZSCHALER

1832

-

Louise Seidler

OTTILIE ARNOLDI

1832

-

Carl Gustav Carus

ALLEGORIE AUF GOETHES TOD

1832