Romanticism was not left untouched by far-reaching political occurrences such as the French Revolution, the rise of Napoleon, and the occupation of parts of Germany. From the German perspective, the 1813 Battle of Leipzig was the single most important encounter in the Wars of Liberation. After his defeat, Napoleon had to retreat across the Rhine, and foreign rule over large areas of Germany came to an end. Many believed the birth of a German nation in unity and freedom was imminent.

Heinrich von Kleist had already written his poem Germania to Her Children back in 1809, calling for a violent end to the French occupation. However, the text was known only to friends and acquaintances to whom he had sent transcriptions. Filled with hatred, ‘Germania’ — the personification of Germany — summons her ‘children’ — the German lands — to take revenge. Not coincidentally, it would be the spring of 1813, two years after Kleist’s death, that the ode would come out in print. Just days earlier, in a personal rallying cry entitled To My People, the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III had appealed to his countrymen for support in the struggle against Napoleon.

For the most part, the Romantic poets joined in the chorus of national enthusiasm, and some even took part in the armed struggle against Napoleon. After the wars had come to an end, many Germans demanded civil liberties and political constitutions from their monarchs. The philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte had already called for the founding of a German national state back in 1808 in his 14 addresses to the German Nation. One consequence of these sentiments was the rise of a militant brand of nationalism as advocated by popular authors such as Theodor Körner and Ernst Moritz Arndt. This development went hand in hand with the denigration and exclusion of all things foreign. The hatred was directed primarily towards the French. However, Germany also saw a rise in anti-Jewish commentaries and writings fuelled by Prussian reform legislation and the ‘Emancipation Edict’ of 1812, which granted civil rights to Jews. Some of the speeches delivered at the German Table Society in Berlin — including those by Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano — bear alarming testimony to racist anti-Semitism.

By the time the Congress of Vienna ended in 1815, it was clear that neither the hopes of liberal reforms nor the longing for a unified German nation would be fulfilled. Events commemorating the Battle of Leipzig — among them the Wartburg Festival of 18 October 1817 — became a pretext for political demonstrations. What had once been progressive political demands now narrowed to a purely national outlook.

The national debate even encompassed matters of dress. Patriotically minded citizens — for example Johann Jakob Willemer, a Frankfurt businessman and the husband of Goethe’s friend Marianne — called for the introduction of a German national women’s costume. However, this “teutsche Frauentracht” never caught on: German ladies continued to favour French fashions.

Objects

-

JUSTIN LÉPANY

Germania an ihre Kinder für 3 Frauenstimmen (Ausschnitt), 2011

Lotta Hultmark (Sopran), Kristina Elfversson (Sopran) und Sabine Eyer (Alt) 2011

-

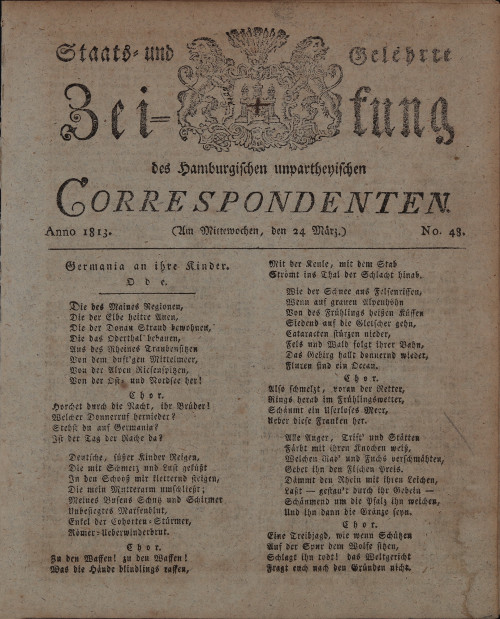

HEINRICH VON KLEIST

Germania an ihre Kinder. Ode

In: Staats- und Gelehrte Zeitung des Hamburgischen unpartheyischen Correspondenten Nr. 48 vom 24. März 1813, S. 1‒2.

-

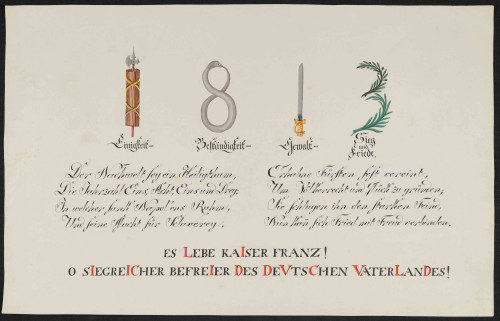

FRANZ-XAVER MILLER

1813. Einigkeit – Beständigkeit – Gewalt – Sieg und Friede

Gratz: Miller 1814.

-

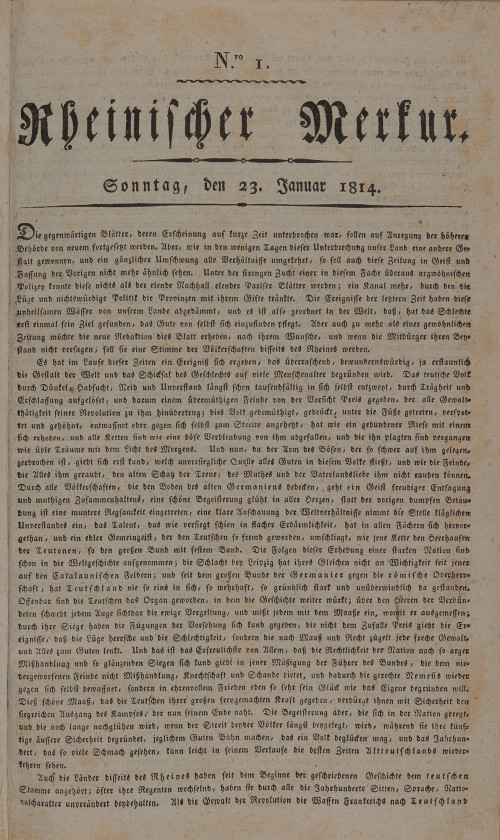

JOSEPH GÖRRES

Vorwort zum Rheinischen Merkur

In: Rheinischer Merkur Nr. 1 vom 23. Januar 1814. Koblenz: Heriot, S. 1‒2.

-

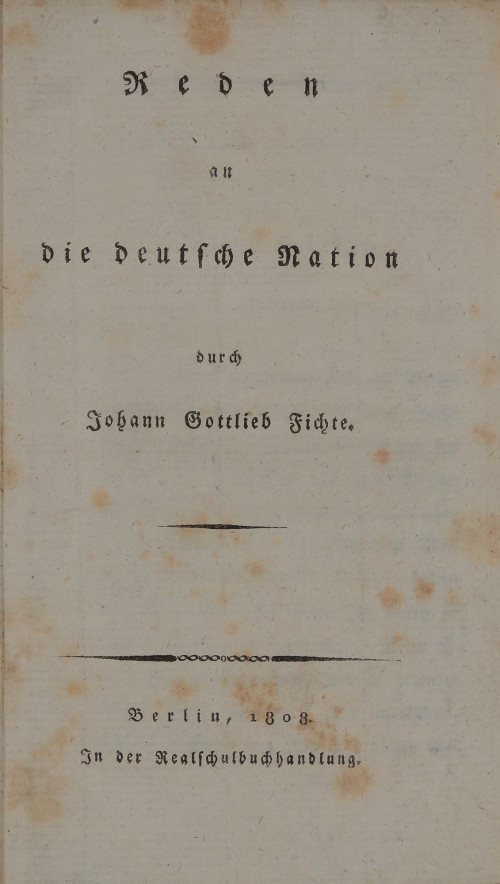

JOHANN GOTTLIEB FICHTE

Reden an die deutsche Nation durch Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Berlin: Realschulbuchhandlung 1808.

-

ERNST MORITZ ARNDT

Blick aus der Zeit auf die Zeit. Von E.M. Arndt

Germanien (d.i. Frankfurt a.M.) 1814 (erschienen: 1815).

-

FRIEDRICH LUDWIG JAHN UND ERNST EISELEN

Die Deutsche Turnkunst zur Einrichtung der Turnplätze dargestellt von Friedrich Ludwig Jahn und Ernst Eiselen

Berlin: Selbstverlag 1816.

-

THEODOR KÖRNER

Zwölf freie deutsche Gedichte von Theodor Körner

Leipzig 1813.

-

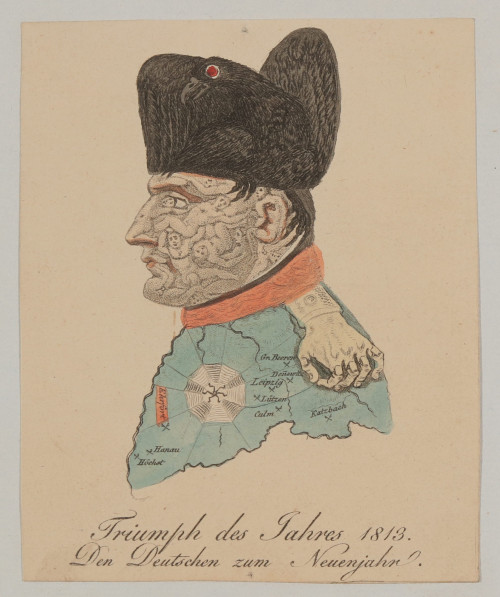

JOHANN MICHAEL VOLTZ

Triumph des Jahres 1813. Den Deutschen zum Neuenjahr 1814

Berlin: Henschel 1814.

-

RUDOLF ZACHARIAS BECKER

Das deutsche Feyerkleid zur Erinnerung des Einzugs der Deutschen in Paris am 31sten März 1814 eingeführt von deutschen Frauen

Gotha: Becker 1814.

-

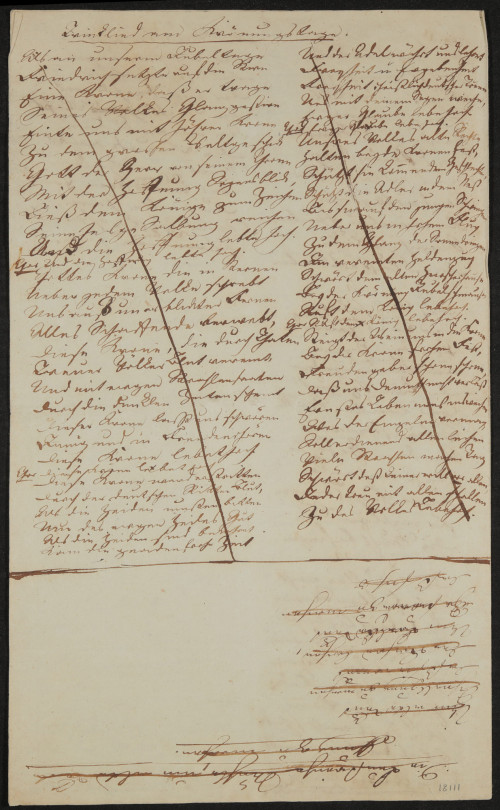

ACHIM VON ARNIM

Trinklied am Krönungstage (vor dem 18. Januar 1811)

-

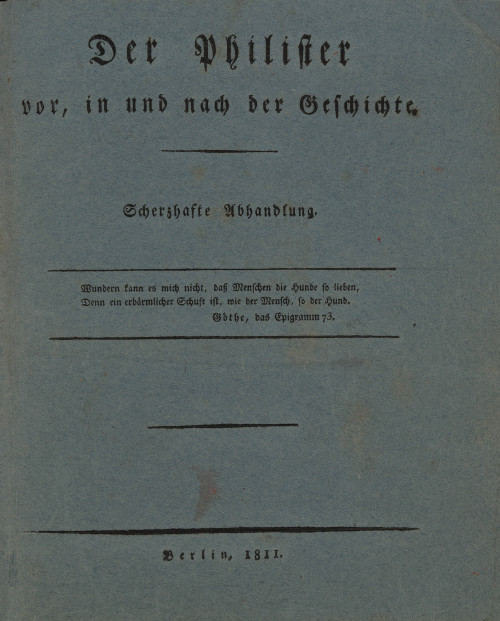

CLEMENS BRENTANO

Der Philister vor, in und nach der Geschichte. Scherzhafte Abhandlung

Berlin 1811.